PLATO’S CAVE

HIGHLIGHTS

Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe. They are a grammar and, more importantly, an ethics of seeing.

(p.3)

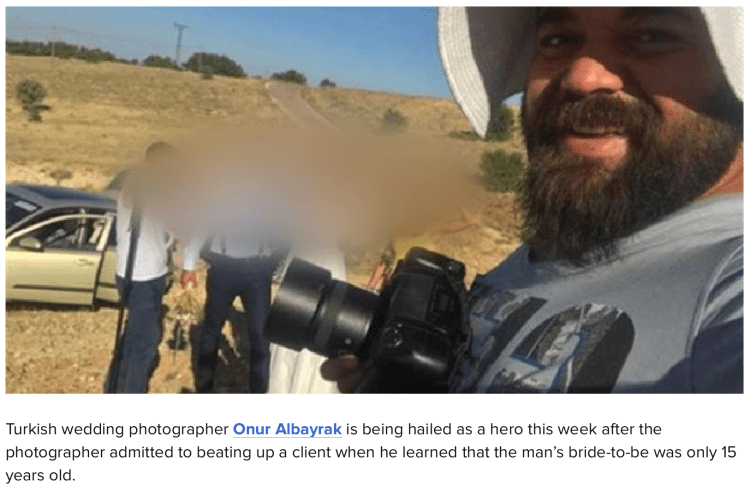

I wholly agree with the above statement; especially when considering street photography, or another situation where consent to take a photograph of someone or on private property is not yet given or not considered. One would argue people have a right to privacy or anonymity in some situations: is it ethical to photograph homeless people without consent? Arguably no, because it is for your own gain (the photograph) and they are vulnerable to how you portray them in a photograph, while already being in a vulnerable state. In the case of Lee Jeffries, it wasn’t until he got consent from homeless sitters that he was able to make meaningful portraits that were used to promote The Salvation Army’s aid for the homeless.

On the other hand, censorship of people or places or objects can have negative consequences, especially when it is subjects that concern or can effect the public. An example of this would be when there was an attempted terrorist arson attack at Bohemian Grove by Richard McCaslin which was prompted by him believing the conspiracy theory that the secretive Boheimian Club’s “Cremation of Care Ceremony” involved satanic human sacrifice. If photographs were allowed to be taken within Boheimian Grove to expose the extreme conspiracies to be untrue, this would not have happened. People only seem to be secretive when they are hiding something incriminating, which causes suspicion.

The closest photographic documentation of Bohemian Grove was made by Jack Latham in his photo book ‘Parliament of Owls’ which focuses on “the dangers of not providing context to the public.”

Photographs, which package the world, seem to invite packaging (albums, framed, featured in magazines and newspapers, exhibited by museums, etc.)

(p.4)

Even when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscious, e.g, FSA 1930s, Dorothea Lange.

(p.6)

In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects.

(p.6)

The omnipresence of cameras persuasively suggests that time consists of interesting events, events worth photographing.

(p.11)

The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene.

(p.12)

In these last decades, “concerned” photography has done at least as much to deaden conscience as to arouse it.

(p.21) (when documenting real life horrific events)

Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.

(p.23)

The omnipresence of photographs has an incalculable effect on our ethical sensibility.

(p.24)

Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted.

(p.24)